FW: “Can’t get rid of the blood?”

Continuing the series of articles about Evidence Collection Training Classes held at SIRCHIE.

Click here for Part 1 – “Have you been fingerprinted?”

Click here for Part 2 – “Where are the Evidence Collection kits made?”

Part 3 – “Can’t get rid of the blood?”

The morning of Day #3 of Evidence Collection Training classes at the Sirchie Fingerprint Laboratories in Youngsville, NC was spent on the tour of the company’s manufacturing facility. We watched as fiberglass fingerprint brushes were made from start to finish, saw riot helmets being assembled, heard the printing presses rhythmically slap logos and directions onto stacks of waiting cardboard, saw employees counting and rechecking boxes of supplies and chemicals. We witnessed a smoothly running facility. That’s what it takes to insure that the products the law enforcement community uses to catch and prosecute the criminals work. Every time, without fail.

After the tour, Robert Skiff (Training Manager/Technical Training Specialist at Sirchie) told us about a new method of fingerprint enhancement developed in Scotland. A bullet can be placed in the middle of an apparatus that shoots electric current into the cartridge and reveals the moisture from a print. This method was demonstrated on an episode of Rizzoli & Isles. Kudos to the show’s writers for including this fascinating technology!

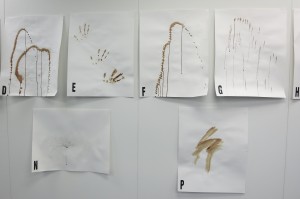

Another interesting piece of equipment is the ElectroStatic Dust Print Lifter. Impressions left at a crime scene in the dust on the floor, or on dusty doors or walls, can now be lifted and preserved. A shot of electricity is applied to foil cellophane and any dust below/behind the lifting mat will stick to it. If there is a palm print or fingerprint, it will show up as a mirror image of the original. Rough floors or brick surfaces where a suspect may have jumped, can now be processed using this lifting method.

Our afternoon training segment dealt with blood and other bodily fluids.

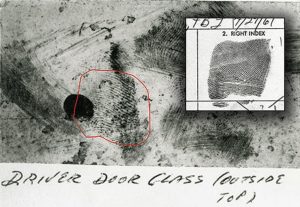

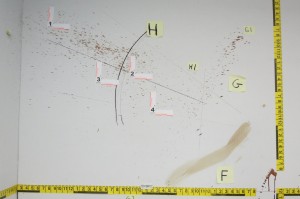

Bloody crime scenes are horrific, but law enforcement officers have to put their feelings aside in order to process and maintain the chain of evidence. Everything they do is aimed at furthering a case to convict, so the scene needs to be secured in order to keep people or animals from contaminating the evidence. If blood is visible at the scene, photographs are taken before the collection process disturbs anything. The photos assist in showing the overall patterns and placement of the drops and splatters. Investigators can determine the approximate place in the room where the victim was first struck, whether the victim was dragged or bludgeoned or shot, if there were one or several victims involved, the velocity of the strike, whether there are arterial spurts, etc.

In order to accurately demonstrate and then analyze the scope and nature of the spatters, the area covered with visible blood is measured and scaled (paper rulers are applied next to the surface being photographed).

Then it is tagged with information that will help the investigators figure out the sequence of events during the commission of the crime.

Specific characteristics of the droplets – whether there is a tail or shaped like an ellipse or a circle, whether small or large circular drops – all reveal information to the investigators and examiners. TV and movie watchers often hear the phrase ‘blunt force trauma’ as a cause of death. This most likely means that the victim has been struck with a baseball bat or a bottle, or a golf club (my fave fictional instrument of death) with medium velocity, so the droplets will be medium sized. (See the drop several inches in front of Mr. Skiff’s finger)

A high velocity hit (from a bullet) will have smaller droplets because the blood is broken into smaller pieces as it leaves the body and is sprayed onto the walls or floors.

Weapons that are close to the scene or involved in the crime, may get blood on them. They need to be processed for blood as well as prints.

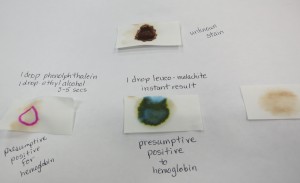

After the visual scans of the room for the visible blood, and the initial photography has been completed, then the areas of possible bloodstains can be swabbed, the samples bagged and identified (as to placement in the room). Presumptive tests can be conducted at the scene, using the Field Kits that contain chemicals commonly used for this purpose. Presumptive tests can help eliminate stains that are not blood, but the stains cannot positively be identified as blood until taken to the lab for confirmation – a detail that TV crime shows frequently fudge.

An added level of security for preserving a sample is to make transfers from the original or take chips of the original, but not test the original. That insures that additional tests can be conducted at a later time on the original or pieces of it.

Three transfers were made from an Unknown Stain and then tested with various chemicals.

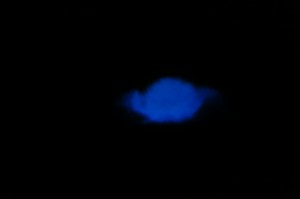

The third transfer was sprayed with a bloodstain reagent, and then the lights were turned off. The Unknown Stain luminesced, therefore indicating the presence of heme, a portion of hemoglobin.

If there is no visible blood in the room, but a crime has been reported as having been committed at that site, it is common practice for investigators to work in teams to process the room. The room is darkened, one investigator sprays the walls with a blood search product, while the other marks (tags) the spots that luminesce. The lights are turned on and then the room is photographed, then processed/tested. The method of spraying and tagging is repeated for floors as well.

It’s worthwhile to note that blood cannot be destroyed with paint. No matter how many coats, no matter what color paint is covering the evidence of the deed, the tests will always reveal that blood has been spattered beneath it. It gets into every crack and crevice. And it just can’t be washed away. Remember the ‘trace evidence rule’? A crook always leaves something behind.

For all you crime show TV junkies out there (I’m one of them): that red blood you see on the bed or wall or floor (hours after a murder has been committed on the show) is strictly for visceral effect. Human blood turns brown or almost black as it dries.

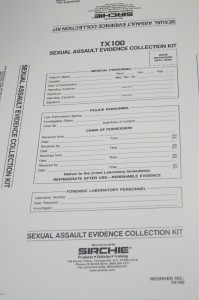

Sexual Assault Collection Kit Record

Unfortunately, reports of sexual assault crimes are on the rise. But, ‘He said, she said,’ cases are difficult to prosecute because there are rarely any witnesses to the crimes. Samples taken from the victims need to be pristine and chain of custody must be clearly established. Clothing and bodily fluids need to be collected from the victim as soon as possible after the crime in order to have a chance of catching and prosecuting the perpetrator. A good practice for evidence collection from victims who arrive at the hospital is to have them disrobe while standing in the middle of a sheet. Then the sheet corners can be pulled together, keeping as much evidence as possible intact. Rape victims may not wish to be touched, but swabbing their bodies for fluids, then bagging and testing whatever is collected, may be the only way to tie a suspect to the rape.

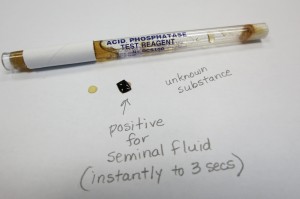

Seminal Fluid Test

A presumptive test can provide important information to include (or exclude) a possible suspect from consideration. There will be an instant (up to 3 seconds) reaction if the unknown substance at the scene or on the victim’s body contains seminal fluid. If the results take longer than that to appear, it must be reported that a false-positive has been found. This might happen if there is not enough of a sample or if the transfer made from the original sample was not good enough.

Rape and homicide evidence is kept for years. Bagged, tagged, stored. Photographed and entered in databases as well. If the suspects aren’t caught right away, then the evidence is still there, waiting in storage, to be matched to other evidence that pops up in later crimes.

*Photos taken by Patti Phillips at SIRCHIE Education Training Center in Youngsville, NC.

FW: “Can’t get rid of the blood?” Read More »