KN, p. 309 “Ammo Casings”

If there are no paragraph separations in this post, please double-click on the title in order to create a more readable version.

It was sort-the-photos week and instead of delete, delete, delete quickly, it took me hours to get through a few albums at a time. Memories and smiles popped up to slow the process. I had forgotten a few of the events, but one from two years ago became the basis of today’s post.

My cousin passed away two years ago next month. For a variety of reasons having to do with a donation his Estate made to a major charity, his possessions had to be inventoried, down to the quantity and types of boxes of bullets. His best friend (a firearms expert and my cousin’s shooting buddy) and I elected to inventory his gun paraphernalia ourselves, in order to expedite matters. In addition to the firearms and hunting gear, the lower level of the house contained equipment for making his own reloads (basically recycled shell casings to make new ammo). It was a hobby that fascinated him and helped reduce the cost of ammo he used at the gun range.

I took photos of everything for the lawyers. I discovered that he had boxes and boxes of shell casings waiting to be worked on, but they were not the same in color or size, since he had a variety of firearms he used in competitions.

This is what I learned: Ammunition casings can be made from five different materials and there are benefits and drawbacks to each.

- Brass

- Steel

- Aluminum

- Brass-plated or Nickel-plated Brass

Each casing material acts differently, so my cousin chose his ammo to fit his activity – practicing at the range, competition shooting, or hunting.

Brass Ammo Casings are known for their consistency in firing, but they are also the most expensive. They are easy to reload and resist corrosion.

Steel Ammo Casings are cheaper than brass and made in many calibers (diameter of the ammo)

Aluminum Ammo Casings are also cheaper than brass and are lighter in weight.

Plated Casings are ammo with a base metal which has been electroplated with nickel or brass. The nickel plating makes it corrosion resistant. Some competitors prefer this version because of its ease of use in a handgun at timed stand-and-shoot competitions.

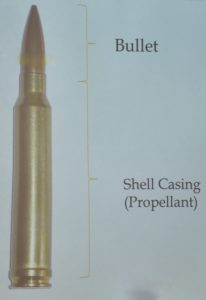

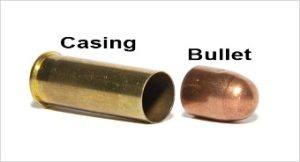

As shown in the photo above, ammo casings are part of the cartridge – not the same as the bullet section of the cartridge. The shell casings separate from the bullet and are ejected from the firearm as the bullet propels forward to the target.

The casings are what law enforcement find on the ground (where a shooter was standing) after shots have been fired in a crime. Patrol Officers and detectives hope that fingerprints can be found on the casings, and that the shooter can be linked to the crime. Careful gun owners pick up their ‘brass’ so as not to litter a gun range, with easily a 100 rounds at a time for each session for each guy/gal. Snipers pick up their ‘brass’ so as not to leave a trace of their having been in that spot. Drug dealers or gun dealers may be involved in a shootout and don’t take time to search for the casings left lying around.

Since the 1990s, there has been a national data base devoted to shell casings: NIBIN – The National Integrated Ballistics Information Network. Run through ATF (Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives) the information is available to most major metropolitan areas in the USA.

Firearms techs enter shell casing evidence photos into the Ballistic ID System, which are then matched/integrated with the database. Local law enforcement is able to search for matches in the system throughout the country, looking for similar crimes, where the casings were found, fingerprints and other information connected with the casings. Over 1,400 law enforcement districts use the database and funding is expanding, as NIBIN continues to demonstrate its benefits.

*Photos of cartridges were taken at conferences.

KN, p. 309 “Ammo Casings” Read More »