KN, p. 310 “The Writers’ Police Academy 2023” by ML Barnes

In 2013, I’d published my second novel, Crossing River Jordan, which had a mild thriller component, and I really wanted to write something with more grit–a serious crime-based mystery. I attended the Writers’ Police Academy, created to help writers “write it right.” The WPA provided a terrific opportunity to learn from law enforcement professionals.

Organized by Lee Lofland, whose law enforcement career spanned 20 years, the Writers’ Police Academy was jam-packed with hands-on workshops, exciting demonstrations, and fascinating lectures, all designed to help writers create believable crimes, characters, and investigations.

Ten years later, and I still haven’t written that book. The 2023 WPA was scheduled to be the last, so I was overjoyed when Patti Phillips shared a free registration so I could attend.

I knew I was in the right place when I arrived at the Hilton Appleton Hotel Paper Valley. The wall behind the reception desk was papered with books and there was a Starbucks in the lobby! I had misjudged the time it would take to navigate highway construction as I drove to Appleton, Wisconsin so I missed the “Touch a Truck and Ask the Experts” event which offered access to public safety vehicles, fire apparatus, CSI Unit, police boats, drones, SWAT vehicles and other equipment on that first afternoon.

I immediately bonded with a group of writers in a spirited search for the WPA registration area. And suddenly, that gritty crime novel was shoved into a mental closet. A group of writers in search of a registration room? No, five writers on a life-or-death scavenger hunt in a haunted hotel. For the rest of my time at WPA, I saw great characters and compelling story ideas everywhere.

That evening, after an orientation, there was a presentation from Mike De Sisti, a photojournalist and creator of The Story in Photos of the Darrell Brooks Trial and Waukesha Parade Attack. A story about a photojournalist and what he does to heal from a traumatic assignment? That would definitely write!

Breakfast at 6 am and then onto buses that transported us to and from Northeast Wisconsin Technical College where our classes for day one were held. First, we had an exciting and entertaining (because of a belligerent suspect) SWAT team demonstration. Afterward, we were allowed to ask questions of the officers and to examine the SWAT vehicle (it was massive!) and equipment.

The best part of that demonstration was the access to real, boots-on-the-ground humans who do the complicated jobs of law enforcement. The officers were surprisingly candid about the difficulties, frustrations, and rewards of everyday policing. I learned that good cops are frustrated by having bad cops on the force and that officers in small cities and towns may have to wear several hats—street cop by day, SWAT officer when needed, meanwhile being trained for crime scene investigation, just in case a crime scene tech is absent one day. Story idea 3 was generated by quotes from the officers: “I get scared too,” and “Good work is rewarded by more work.”

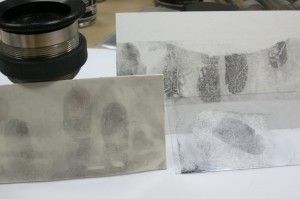

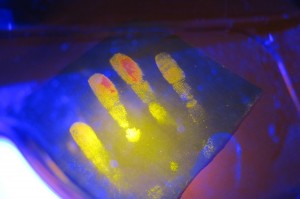

Later I attended Crime Scene Investigation taught by Dan Feucht and his protege-turned-partner Holly Maas. It was an in-depth lecture and hands-on workshop. I got to do a palm-print transfer! Holly Maas is a civilian crime scene technician, married to a cop and mother of three boys. Awesome character, right?

I’d originally wanted a different class than the one I attended last and now, I don’t even remember what that class was. K9 Emergency Aid presented by Dr. Lisa Converse was riveting! The OPK9 program is designed to provide prehospital care education to first responders assisting Operational K9s. Dr. Converse’s training has been responsible for saving the lives of K9s injured in the line of duty. I don’t write animal stories, but I saw so many possibilities for tales of courageous K9s and their handlers.

Death by Powders and Pills was my first session the next day, taught by Drug Recognition Expert Nick Place an officer with more than 21 years in law enforcement. We learned about the current scourge—fentanyl—and how fake drugs are being used to get people addicted to opioids. We learned how easy it is to make pills and how much of the equipment and ingredients are available online from our favorite retail distributors. We even made a pill using baking soda. I came away from this class with a story idea about rival gangs and their problems with marketing.

Cold Cases, taught by Det. Sgt. Bruce Robert Coffin began with our learning the first Rule of Cold Case investigation: “You don’t know anything.” I loved this session because Coffin was himself a character, dry witted, cynical and wise. He gave us information from the perspective of a cop AND a writer. I bought two of his novels at the WPA bookstore later that day.

A final awesome benefit of the Writers’ Police Academy is access to other authors on every rung of the literary ladder. Insight advice, commiseration and delight filled every spare minute as we chatted during meals and breaks, on the buses and in the moments before evening activities. In addition to meeting keynote speaker, Hank Phillippi Ryan, I also got to know several amazing women for whom writing is more than a hobby. That kind of inspiration is priceless.

Lucky for writers, the WPA is retooling for next year, rather than closing its doors, as was the original plan. I hope to see everyone there!

*****

Many thanks to Mari Barnes for writing about her terrific experiences at the 2023 Writers Police Academy! The classes she attended were led by experts from all over the country and are the source of invaluable research for future works.

Click on the titles to take you to more information about her novels:

“Parting River Jordan”

“Crossing River Jordan”

Find Ms. Barnes’ “Grow Your Story Tree: A Writer’s Workbook” here.

Her publishing company, Flying Turtle Publishing, can be found here.

*Photos provided by ML Barnes.

Bruce Coffin’s headshot is courtesy of his website.

KN, p. 310 “The Writers’ Police Academy 2023” by ML Barnes Read More »