If there are no paragraph separations in this article, please double-click on the title to create a more readable version.

August, 2019 note: I had occasion to return to SIRCHIE during MurderCon, a Writers’ Police Academy event. While the instructors were different, it’s reassuring to note that the science remains the same. Read on for details about gathering fingerprints from paper.

People ask me all the time how I acquire the information needed to write Kerrian’s Notebook.

Simple answer: research. And lots of it.

If the questioners want to know more, I mention the conferences I attend, the reference books I read, the internet sources I’ve tapped into, and the experts willing to chat about their chosen fields. It’s a fascinating part of the job and I love it.

The next few posts will reveal some of the information gathered at a series of classes where I took photos and lots of notes. If you’re a regular follower of Kerrian’s Notebook, you may recognize some of the details mentioned here as having appeared on previous Detective Kerrian’s pages.

For all out fun, I go to the Writers’ Police Academy – this was the 5th year at the Guilford County, NC location (my fourth). It’s a three-day, mind-blowing experience that demonstrates the nuts and bolts of police and fire and EMS procedure – taught by professionals and experts actively working in the field.

Along with several other strands of study, the 2011 WPA conference provided classes in bloodstain patterns, fingerprinting, and alternate light sources (ALS) conducted by Sirchie instructors. Because of the standing room only enthusiasm for these classes, Sirchie offered a five-day Evidence Collection training session for writers at their own complex in North Carolina. Sirchie makes hundreds of products for the law enforcement community and I felt this would be a great opportunity for Detective Kerrian to learn more about the latest and best gadgets being used to catch the crooks.

I happily sent in my application and plunked down my credit card to hold my space in the class – ten months ahead of time.

On the first day of classes, our instructor, Robert Skiff (Training Manager/Technical Training Specialist at Sirchie) discussed the ‘CSI Effect’ – the pressure placed by the popular TV shows on real life crime investigation. TV labs and real life investigations bear little resemblance to each other – not in time, or equipment, or budgets. Then we got to work, using the powders and brushes needed to process a crime scene and used by actual techs in the lab.

It’s up to investigators and examiners to prove the case against the suspects, using proper evidence collection techniques and tools, because trace evidence is ALWAYS left behind.

Fingerprints found at the scene are still the favored piece of evidence tying the suspect to the crime. These days, using a combination of ingenuity and newly developed chemicals and powders, a crime scene investigator can lift (and/or photograph) prints from many previously challenging surfaces.

By the way, black fingerprint powder gets all over everything when newbies are handling it for the first time. We must have used 50 wet wipes each during the morning alone.

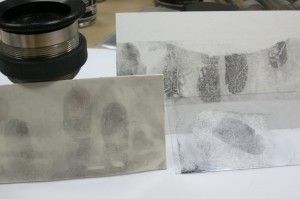

After dusting prints with black fingerprint powder,

they were lifted from various smooth surfaces using (in forefront) a gel lifter, a hinge lifter and (in background) tape.

Our prints were photographed and then viewed under an Optical Comparator. This machine can be hooked up to a laptop, and the image sent off to AFIS for identification purposes. No crooks in our crowd, so we omitted that step.

Did I mention that we had loads of fun?

On the second day, Robert Skiff’s assistant for the class, Chrissy Hunter, passed out stainless steel rectangles and we pressed our fingers onto the plates, twice. First time – plain ole print, second time – ‘enhanced’ by first rubbing our fingers on our necks and foreheads to increase the amount of oils in the print. The ridge detail in the prints was so clear in the ‘enhanced’ version that there was no need to process them with powder. We lifted them with a gel lift.

If we were working a real scene, that might never happen, but it could. The usual occurrence is that partial prints are left at the scene and that’s what makes the search for the suspects so much tougher than what the TV dramas indicate. There is no instant ‘a-ha’ moment that comes 45 minutes after the crime has been committed.

The prints are generally sent off to be compared with the millions in the AFIS database, and here’s where TV parts with reality again. AFIS comes back with a list of 10-20 possible matches and someone then makes a comparison by hand of the most likely hits.

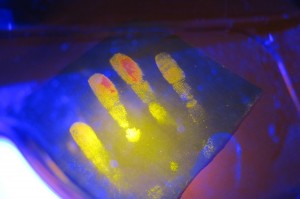

After practicing the basics, it was time to move on to fingerprint discovery on documents. There are scheming relatives who forge wills, less than loving spouses who murder for the insurance, bogus suicide notes, and the list goes on. How to prove the nefarious intent? Fingerprints. But…as we discovered the first day, fingerprint powder is messy and almost impossible to clean up. An important document could be destroyed in the search for evidence of foul play. Enter chemicals and alternate light sources (ALS).

Iodine

DFO

Ninhydrin

Silver Nitrate

MBD

If used in this order, the sample won’t be compromised, even though treated several times over several days. We experimented with several chemicals with excellent results, but for the ‘wow’ factor, I’m showing the ones that look great on camera.

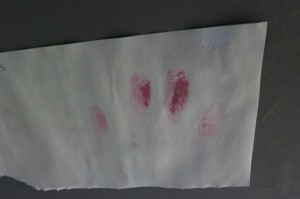

DFO reacts to amino acids in the prints. We created our samples placing our own enhanced prints on plain white paper. We hung the papers in the fume hood, saturated them with DFO, then put them in the oven to bake for several minutes.

After we sprayed our samples with DFO and baked them in the oven, we darkened the room, and put on orange plastic glasses. Then we side-lit the sample with a 455nm light. The photo was taken at that point.

Same sample, side-lit at a slightly different angle. Photo taken through an orange filter.

Before working with any chemical, it’s a good idea to make copies of the document. Why are there different kinds of Ninhydrin? Zylene will run some inks. Acetone will run all inks, all the time. Ooops! There goes the document if you grab the wrong chemical, so copies are definitely necessary. Noveck is the clear winner when working with inks. It gets fast results and dries quickly. Additionally, it can be sprayed on an outer envelope to reveal what’s inside. Without damaging either piece of paper. Very cool.

You could see the plots developing in our writerly minds as the Noveck dried and the words inside the folder faded from view.

*Photos taken by Patti Phillips at the Sirchie Education and Training Center in Youngsville, North Carolina.