KN, p. 141 “What does a CSI tech really do?”

If there are no paragraph separations in this article, please double-click on the title in order to create a more readable version.

TV makes the job of a CSI tech look like a lot of fun.

It looks like an easy job, too. Get a call from dispatch, arrive at a crime scene, pop on the gloves, shine a flashlight around, take a few photos, collect the evidence along with your team of 4-5 colleagues and go back to the lab an hour or so later, ready to process all of it.

Have the real CSI techs and law enforcement professionals stopped laughing yet? 😉

Here’s the reality:

Most small towns (under 50,000 people) have no CSI lab. None. The local police in smaller towns are able to collect fingerprints, but most have to send them off to a State Lab to be processed.

Many towns, even with a population of 100,000 people, don’t have a ballistics lab to check the caliber of any bullets/casings left behind at the scene or found in the victim’s body.

North Carolina (as of 2022) had a population of 10.7 million, and has three State crime labs – one full service and two regional labs.

New York State (as of 2022) had a population of 19.68 million, and has four State crime labs – one full service and three specializing in varied areas.

New Jersey (as of 2022) had a population of 9.26 million. It has seven State labs.

Texas (as of 2022) had a population of 30.03 million, with a full service forensic lab in Austin and 14 regional labs, some conducting only drug testing, and others close to full service.

And all of those crime labs are processing evidence from all kinds of crimes (burglary, robbery, rape, arson, cold case, assault, etc.) not just murders. It take a few hours to get the prints, preserve the evidence, bag and tag it for transport, but it takes months to get it processed, because there is a long line of cases ahead of yours. In some States, the wait is as long as 18 months. That is not a typo, folks. Eighteen months to wait until the evidence can be processed. Even if the case is a high profile one, moving to the head of the line might only shorten the wait to 2-3 months, because there are other high profile cases in line as well or cases that are already in court, waiting for clarification of the evidence.

There is no such thing as instantaneous fingerprint matches. See the article about fingerprint analysis here. There are now handheld machines that scan a viable fingerprint at the scene, but that only speeds up the collection process, not the identification of the fingerprint. (I was recently told that a new fingerprint reader can return an answer in 45 seconds, but some fingerprint experts are reserving judgment as to the accuracy of the matches.)

Get the picture? The State Bureaus of Investigation are short-staffed and the cases more numerous, as attorneys seek to prove or disprove beyond the shadow of a doubt that the evidence gathered at the scene linked their clients to the crime.

In general, the analysts examine all types of evidence related to criminal investigations and assist the criminal justice system. They can provide:

- Consultation on the value, use, collection, and preservation of evidence,

- Analysis and comparison of evidence from crime scenes and/or people,

- Expert testimony in court proceedings, and

- Assistance for collecting evidence and processing crime scenes,

- Forensic science information to law enforcement agencies and district attorneys.

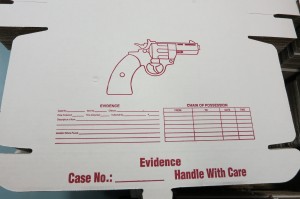

ALL of that evidence must be collected in a thorough and efficient manner by the Crime Scene Technician or Crime Scene Investigator. Cases are won and lost on how the evidence is handled – both the chain of custody and the collecting of the correct evidence can be factors in how a suspect is perceived.

I had a chance to chat with a CSI who has been in the field for about 10 years. She generously shared information about her day – soooo different from the image of the CSI jobs projected on TV.

She enters a crime scene after a Patrol Officer has cleared the house (made sure that no unauthorized person is in it). A Deputy might walk her through the house, and depending on the crime, the owner of the house then walks her through, pointing out items that might have been disturbed or areas where items are missing. She takes notes during the tours so that she can come up with a Plan of Action – how to process the scene.

In general, she will take photos first, and then collect the evidence. If a homicide is suspected, she might take video as well as still photographs.

She might see patterns of wreckage, or concentration of destruction, or even similarities with other cases, but it is not her job to focus on the M.O. (modus operandi) or narrow her collection efforts based on a hunch. She is there to collect all the evidence.

She might be looking for:

- Fingerprints

- Blood spatters

- Fibers

- Footwear impressions

- Tire impressions

- Tool impressions

- DNA samples (hair, nails, blood, saliva, etc)

- Murder weapon

- Point of entry

- Kinds of items taken

What a CSI leaves at the scene is sometimes as important as what he/she collects, so it is vital to be thorough. The detectives and attorneys decide what is significant to the case.

The trunk of a CSIs car is filled with the tools of the trade. They have kits for each type of evidence collection and if they know in general what the scene will call for, they may grab an additional kit from headquarters. They might even carry a tarp to cover the ground (creating a collection place for the evidence) if the scene is outdoors – such as a train wreck.

The CSI I interviewed works in Major Crimes for the Sheriff’s Department, and when she is called to a scene, she works 12-hour shifts, by herself. In most cases, she collects all the evidence, bags and tags it appropriately, and hands it all to the detective in charge. She works 14 days a month, equally divided between the day shift and the night shift. On occasion, a 12-hour shift is not long enough to collect everything at a particular crime scene, so she stays a bit longer to finish. If it looks as if she has to work for another shift, a Patrol Officer will guard the scene until she returns to finish collection on her next shift. If the case merits 24-hour collection (because of weather or the condition of the scene/body) the CSI on the next shift will continue the collection, with any evidence collected up to that point handed over to the new person.

Clear chain of possession of the evidence dictates that in a case where collection goes on for more than one shift, limited people will have keys to the building. There are evidence cards showing who collected it, and anyone entering or leaving the scene will have to sign in and out with the Patrol Officer on duty.

For information about Footwear Evidence, click here.

Next week: The life of a CSI – rewards and challenges.

*Photos taken by Patti Phillips

KN, p. 141 “What does a CSI tech really do?” Read More »