KN, p. 261 “Forensics – What’s It All About?”

If there are no paragraph separations in this article, please double-click on the title to create a more readable version.

Forensic: relating to or dealing with the application of scientific knowledge to legal problems (Merriam-Webster dictionary definition)

Back when I began in the Police Department (longer ago than I care to admit) the word ‘forensic’ was rarely used by police officers on the street. We knew to be careful if we were first to arrive at crime scene so that potential evidence wouldn’t be compromised, and the detectives pointed us to what needed to be preserved or uncovered so that a case could be proved. We dealt with physical collection, not analysis.

Analysis of the evidence is in the purview of the forensic scientists, the detectives, and the D.A.’s office.

Forensic Science is the broad term encompassing a wide range of forensic specialties and these days, is often shortened to ‘forensics,’ as in: ‘Let’s take a look at the forensics on the case.’ But what area of forensic science is required to solve a case? It depends. The prosecutor doesn’t need the findings from a dental x-ray when dealing with a known victim, but might need the results of a forensic toxicologist’s tests to determine a seemingly suspicious cause of death.

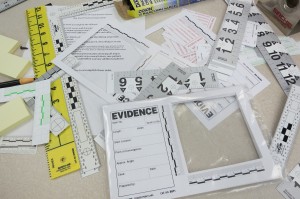

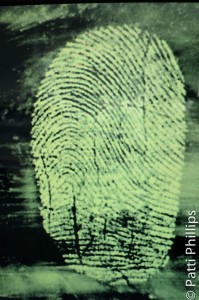

Most evidence is collected from the scene of the crime by trained local law enforcement personnel (that includes the photographer and the fingerprint person) in smaller jurisdictions, specifically assigned crime scene investigators (CSIs) in larger municipalities, and if needed, the forensic scientists themselves.

For the most part, the processing of body evidence is completed in labs or during autopsies in hospital, police, or State morgues. Other than body tissue or bodily fluids, things that shouldn’t be there (bullets, metal fragments, gravel, etc.) are sent out for testing. Experts might be tapped for their opinions about certain marks on the body that would have caused a blunt force trauma or other types of violent death, or for the condition of recovered remains.

Non-body evidence would be gathered from the scene and sent for processing to a lab that specializes in that area of analysis. Most States in the USA have centralized labs for various umbrellas of expertise, since smaller towns just don’t have the financial wherewithal (equipment and personnel) to handle finite investigations. In these days of post CSI TV shows, prosecutors and defense attorneys alike need to nail down the suspect’s guilt with absolute certainty for the public, so they rely on forensic test results and/or experts in the field to convince the jury of a suspect’s guilt or innocence.

So, who does what and how do they help the prosecution or defense teams? Listed below are some of the many forensic specialties.

Bloodstain Pattern Specialist determines the point of origin of an impact pattern as well as the movement of people after being hit or shot.

Digital Forensic Analyst recovers or investigates data from electronic or digital media, including audio and video recordings, and computers. These days, the skill set may also include the ability to investigate cellphones and other mobile devices for the call history, deleted messages, and corrupted SIM cards.

Forensic Accountant finds accounting discrepancies and interprets them for fraud or tax evasion cases as well as other criminal activities.

Forensic Anthropologist helps identify skeletonized human remains.

Forensic Ballistics expert investigates the use of firearms and ammo from a crime scene.

Forensic Botanist can determine where a body or suspect may have been because of the plant life found in or around the body or suspect.

Forensic Chemist detects and identifies illegal drugs seized during a drug bust, or found in a body.

Forensic DNA analyst does paternity/maternity testing or places a suspect at a crime scene.

Forensic Document Examiner interprets document evidence to determine authenticity of wills or potential forgeries.

Forensic Entomologist exams insects in, on, and around human remains to help establish the time and place of death.

Forensic Facial Reconstructionist works with the skulls of recovered remains to identify them.

Forensic Geologist analyzes trace evidence establishing where a body was killed or whether it was moved to a different location.

Forensic Limnologist analyzes evidence collected in or around fresh water sources. Examination of biological organisms can connect suspects with victims.

Forensic Odonatologist compares dental records with teeth of the corpse when facial recognition isn’t likely or possible.

Forensic Pathologist applies principles of medicine and pathology to determine a cause of death or injury for legal purposes.

Forensic Photographer creates an accurate photographic record of a crime scene to aid investigations and court proceedings.

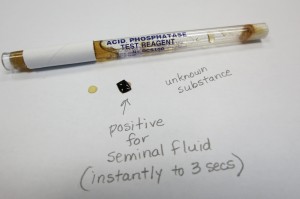

Forensic Serologist tests body fluids for rape cases or to determine if blood on the body belongs to that person or someone else.

Forensic Toxicologist analyzes the effect of drugs and poisons on the human body.

Trace Evidence Analyst analyzes trace evidence including glass, paint, fibers, hair, etc. that occurs when different objects contact one another.

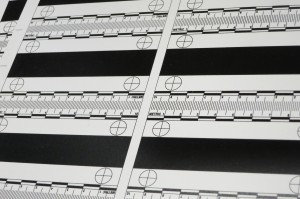

Shoe companies, gun manufacturers, tire companies, etc. all keep records of their products made and distributed over time. In the age of computers, some enterprising criminalists created a variety of national databases with information on multiple companies and their products. The goal? To make it easier to match up shoe prints, or skid marks, or bullets to a particular person or crime scene. With a little luck, and research/chemical testing, even filed down serial numbers can be revealed, and a firearm can be traced back to its manufacturer, point of sale, and the owner. Tire impressions at a crime scene can be matched to a database to discover the make and model of a vehicle that may have been there. Distinctive shoe prints in the mud outside a house can be matched to a suspected burglar, or rule him/her out.

Who makes sense of all of the information observed and gathered at a crime scene? Generally, it’s a team effort, not the achievement of just one person that heroically solves the mystery of the who, what, when, where, and why of a crime scene. But the Forensic Scientists (or Criminalists) play a big role in identifying the pertinent pieces of the puzzle. They can answer questions about what they discovered while comparing body evidence, trace evidence, fingerprints, footwear impressions, drugs, ballistics, paper trails, etc., and the detectives or investigators most familiar with the case pull it all together.

Who makes sense of all of the information observed and gathered at a crime scene? Generally, it’s a team effort, not the achievement of just one person that heroically solves the mystery of the who, what, when, where, and why of a crime scene. But the Forensic Scientists (or Criminalists) play a big role in identifying the pertinent pieces of the puzzle. They can answer questions about what they discovered while comparing body evidence, trace evidence, fingerprints, footwear impressions, drugs, ballistics, paper trails, etc., and the detectives or investigators most familiar with the case pull it all together.

Somebody asked me recently if just anyone can tack ‘Forensic’ in front of their job title. Not likely. For instance, a Forensic Accountant is much more than a savvy bookkeeper. They have advanced degrees and certifications specifically geared toward discovering whether a crime has occurred in complex situations, evaluating whether there might have been criminal intent, and then communicating that information in a way that a layperson can understand it. From Investopedia.com: “The reason we understand the nature of Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi scheme today is because forensic accountants dissected the scheme and made it understandable for the court case.”

This level of expertise is required in every area of forensic analysis.

Related articles:

“Who Murdered Jake?” in Kerrian’s Notebook, Vol. 2: Fun, Facts, and a Few Dead Bodies

*Photos by Patti Phillips

KN, p. 261 “Forensics – What’s It All About?” Read More »