KN, p. 222 “Underwater Evidence and Body Recovery: Lakes and Bodies of Water”

Warning: article contains details about dead bodies.

Warning: article contains details about dead bodies.

Crime scene tape has been posted around your favorite big pond or lake and nobody can get on/in the water until it has been searched. What has happened? Perhaps a body has been sighted underwater by a swimmer, or a fisherman has snagged something suspicious on his hook. A violent crime may have been committed in the area and the police are looking for discarded weapon(s). Or a report has come in to the police station about a missing person, and that missing person may have been seen in the vicinity of the water. Law enforcement is already on the case and if the crime scene tape is up, along with officers conducting an investigation, then a dive team is most likely working your formerly peaceful spot.

The USA has a great many lakes and assorted other bodies of water, both natural and man-made. Just a few examples:

Alaska: over 3,000,000 lakes (yes, 3 million)

Minnesota: 10,000 lakes (it’s even written on the license plates)

New Jersey: 366 named ponds, lakes, and lagoons

North Carolina: 78 named lakes as well as several bays, sounds, and hundreds of ponds.

Texas: over 200 large lakes and reservoirs.

When that many bodies of water are part of the landscape, it makes sense that the Sheriff’s Department (County law enforcement) and First Responders have teams that specialize in underwater evidence and body recovery. Why the Sheriff’s Department? It’s not about deep pockets financing the operations, it’s all about jurisdiction and best use of available resources. Many large lakes cross town lines, and the Sheriff’s Department has jurisdiction in all the towns in its County. No need to duplicate personnel, when prevailing thought is that one or two teams per County will be able to handle the job of underwater evidence and body recovery.

Note: the local Fire Department usually has a First Responder team on the site of any accident – they are trained for rescue. At some point, it will be determined whether it is a recovery or a rescue and/or if there is a need to preserve evidence. It’s usually a recovery rather than a rescue at a lake, because after a person spends ten minutes under the water without air, it becomes a recovery operation.

Are there enough on-the-water deaths to make certified-for-recovery dive teams necessary? Sadly, yes. The Great Lakes Surf Rescue Project tracks those stats for the five biggest USA lakes. There were 99 deaths reported in 2016, 88 in 2017, and as of this writing, 47 so far in 2018 in the Great Lakes alone. North Carolina has reported 10 lake deaths so far in 2018.

Most of the time, the lake deaths are accidental, but on occasion, bodies are found because of a homicide.

A body will float after 72 hours, and continue to float for a couple of days. After that, the naturally occurring body gas is expelled and it will sink again. Bodies are often found fairly quickly, but a body gets like jelly if it’s been in the water for a while, complicating the collection process.

Cold water will preserve a body, and warm water will cause more rapid decay, so divers must work carefully in the warmer locales. Cadaver dogs can pinpoint the location of a body to speed up the work. It’s been discovered that the longer the body is in the water, the wider the smell arc for the dogs. It’s a little like a dead fish smell, more concentrated closer to the body.

If no cadaver dogs are available, the divers swim in ever bigger arcs from the chosen starting point onshore and they work in grid patterns. If the search area is large enough, one of the onshore/on boat team members keeps a map/record of the searched areas.

In general, when working in shallow water, the investigation and recovery can be accomplished by dive teams alone. In deeper water, it will be a combination of boats and dive teams that do the search and recovery.

Most dive teams have the same equipment. They dive with aluminum scuba tanks and 3200 pounds of air will last about an hour. The basic dive suit is worn for warmth and protection – below 10 feet, it’s cold, no matter what the weather is up top. They also have hazmat suits to dive with in toxic environments.

Buoys are color-coded and are released to show when the diver(s) need help or when marking the spot.

With the smallest team of 3 people, there are:

- Diver

- Safety diver

- Surface tender

With a team of 11 people, at any given time, there are five people in the water.

It is protocol to always keep one diver on the surface, ready to assist under water or switch places with the diver already in the water. The “tender” stays on the surface (whether in a boat or on the shore) and directs the search using a rope. The tender signals by tugs; he/she lets the rope play out, and then gives more when needed.

The “tender” not only controls the line and the search pattern, but keeps track of the air time and the clock time on a log, which becomes the official record of the diver/search activity. If there is a new diver on the team, the tender tracks to see the average air use, an important stat to have when making sure a sufficient supply of air tanks is on hand for each team member. The tender can estimate the time/air left in the tanks in use after observing the previous pattern of intake by the newbie.

After spending time in the water, the divers will be dehydrated, another thing the tender keeps track of.

Stay tuned for Part 2: “Searches.”

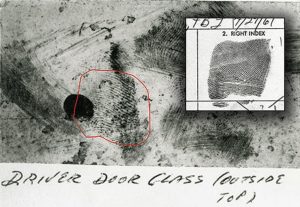

*Photos taken by Patti Phillips at two Writers’ Police Academy events in North Carolina. Many thanks to Lee Lofland for organizing the annual events, and to the members of the Guilford County Sheriff’s Department for their informative presentations.

KN, p. 222 “Underwater Evidence and Body Recovery: Lakes and Bodies of Water” Read More »