FW: “Where are the Evidence Collection kits made?”

If there are no paragraph separations in this article, please double-click on the title to create a more readable version.

NOTE: This was updated in August, 2019 to reflect new information. 🙂

Part 2 – information about Evidence Collection Training Classes held at SIRCHIE.

Click here for Part 1 – PW: “Have you been fingerprinted?”

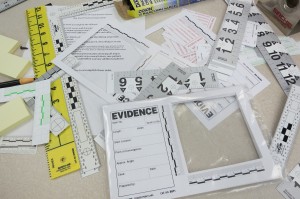

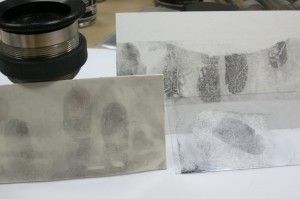

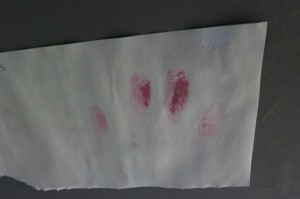

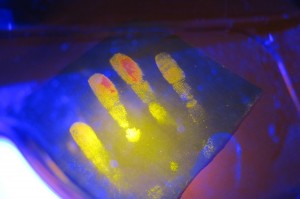

During the first two days of Evidence Collection Training, we used a number of chemicals, fingerprint powders, and brushes, and employed several different fingerprint lifting techniques on a variety of tricky surfaces. We discussed the benefits of both cheap and costly Alternate Light Sources.

Our notebooks were filling up and theories of the perfect crime were flying around the class. We kept quizzing Robert Skiff, our instructor, (Sirchie Training Manager/Technical Training Specialist) about ways to ‘get away with the murder of the decade.’ But, as we learned, there is no perfect crime. That pesky trace evidence will always be waiting at every scene for the investigator to discover it, photograph it, tag it, bag it, and transport it without losing the integrity of the sample.

It was time to visit the plant – see how the powders, brushes, and other crime scene paraphernalia were made.

Sirchie manufactures most of its products in-house. The specialized vehicles for SWAT, bomb rescue, arson investigation, and surveillance work, etc., will now be built in North Carolina, along with the smaller products.

Security was carefully controlled throughout our tour. Most of our group writes crime fiction, so we are always looking for a way our fictional criminals can break in (or out of) a wild assortment of locations. As we walked through the stacks and aisles of products, we commented to each other on the smooth organization and many checks Sirchie had in place. Cameras everywhere. Limited access to the assembly floor. Labyrinths a person could easily get turned around in. If we got separated from the group while taking an extra photo or two, we were found and escorted back by an always friendly employee.

Of course, we couldn’t turn into rogue students anyway. Our fingerprints littered the classroom and they knew where we lived.

Security plays a part in the assembly model as well. Each product they create is put together from start to finish by hand. There are no assembly lines because of trade secrets and a dedication to preserving product integrity. Personnel are carefully screened before being hired and qualification for employment includes graduate degrees. No criminal history whatsoever is allowed. Every employee comes through the Evidence Collection Training Class so that they understand what Sirchie does as a whole.

Templates for the various products are created in-house. The operators of these machines are highly trained experts. Quality control is paramount, so training is constant.

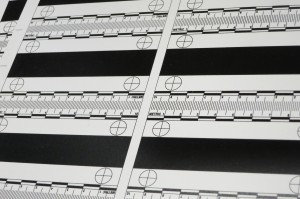

All the printing is done in-house. The printing area was stacked with cases of items being packaged for shipment. We saw strips large enough to process tire treads.

Field Kits are created for general use by investigators, but can be specifically designed for a special need. The small vials contain enough chemicals to test unknown stains and substances at the scene. Note the dense foam holding the vials and bottles firmly in place. The kits are usually kept in the trunk and probably get tossed around quite a bit. The foam insures against breakage during car chases and while bumping across uneven road surfaces.

There are fiberglass brushes, feather dusters for the very light powder, regular stiffer brushes, and magnetic powder brush applicators.

We were lucky enough to see fiberglass brushes being made.

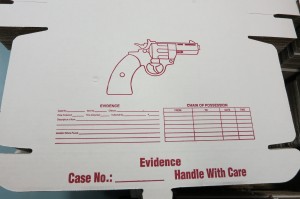

If a handgun is seized for evidence, there needs to be a simple, yet effective way to track chain of possession.

*Bag the gun to preserve the fingerprints and

*drop the gun in the box.

*Then fill in the blanks on the box.

*Easy to stack and store until needed.

Think of all the cases that may be ongoing in a large jurisdiction – the evidence is not sitting at the police station. It’s in a warehouse someplace, and needs to be easily identified when required for court. In addition to several sized boxes for guns and knives, etc. Sirchie also provides an incredible assortment of resealable plastic bags for preserving evidence like clothing, unidentified fibers, etc.

Magnetic powder was being processed that day and then put into rows and rows of jars and jugs. Before it is sent out to the customers, each lot is tested for moisture content, appropriate ratio of ingredients and other trade secret tests. We joked about taking some back to class for the next round of fingerprint study and were surprised by how heavy the jugs were.

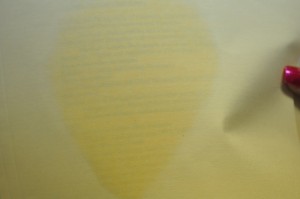

No, she’s not making bullets. She is assembling the cyanowand cartridges used for fuming with superglue.

SIRCHIE makes riot gear.

This is not a photo of something from a SyFy movie. At the center of the shot is a helmet template. The drills encircling the template are aimed at spots where holes are needed for each helmet, depending on the type of helmet in production. All the holes are drilled at the same time.

The Optical Comparator, as well as the other machines, is built to order by hand.

While in the warehouse, we learned that if a product is discontinued, it is still supported by Sirchie. That means that if a law enforcement officer calls up with a problem a few years after purchasing a machine, he can still get help. Reassuring for jurisdictions with a tight budget that can’t afford to replace expensive equipment every year or two.

Sirchie sends supplies to TV shows, so next time you’re watching a fave detective or examiner lift prints with a hinge lifter, it may have come from Sirchie.

Thanks to Lee Lofland, host of Writers’ Police Academy, for the opportunity!

*Photos taken by Patti Phillips at the Sirchie Education and Training Center in Youngsville, North Carolina.

FW: “Where are the Evidence Collection kits made?” Read More »